An Iron Age Bowl from Tullen, Co. Roscommon

By independent woodworking specialist Caitríona Moore and senior archaeologist Ros Ó Maoldúin of Archaeological Management Solutions

Excavations in advance of the N5 Ballaghaderreen to Scramoge Road Scheme in County Roscommon led to the discovery of over 100 previously unrecorded archaeological sites revealing evidence of human activity in the area extending from the Mesolithic to modern times. Here we highlight a particularly well-preserved Iron Age alder bowl found during an excavation (reg. no. E5142) directed by Lydia Cagney in Tullen townland, just north-west of Scramoge.

The Tullen Bowl (Photo: John Channing, AMS)

The Tullen Bowl (artefact no. E5142:4) was found in the upper fill of a large pit, interpreted as a well, on a burnt mound site called Tullen 2. (A video documenting its recovery can be viewed here.) The bowl has been radiocarbon-dated to the latter half of the Middle Iron Age (196 BC–AD 6) and a sample of hazel charcoal from the base of the well was dated to the Late Bronze Age (1256–1019 BC). Dates from other features on the site indicate that it was also in use from the Chalcolithic (Copper Age), and during the Early Bronze Age.

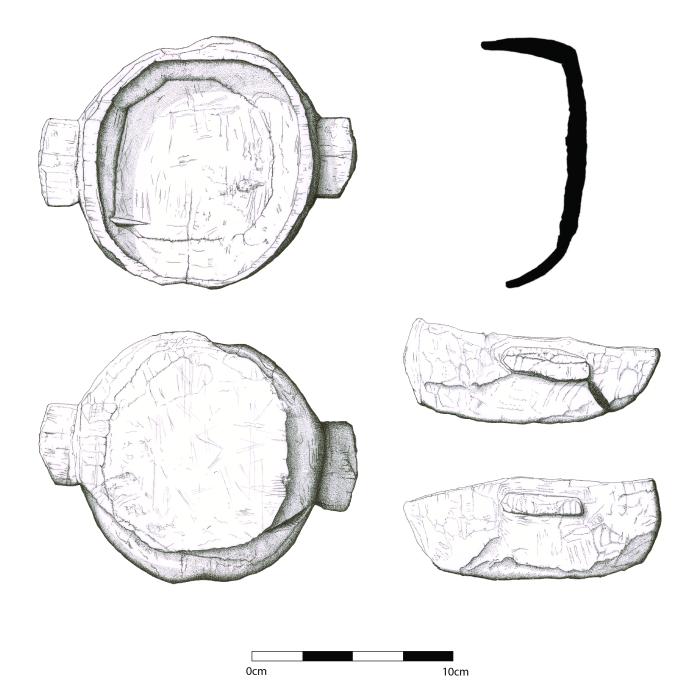

The bowl was carved from a single piece of wood and is subcircular, measuring 202–223 mm in diameter internally and 235–248 mm externally. A pair of opposing horizontal lug handles extend the maximum external length to 316 mm. The thickness of the wood varies from 5.6 mm to 30 mm. There is one crack in the vessel wall close to the base; however, overall, it is in excellent condition. The rim is flat and worn, with an average width of 17 mm. The walls are mostly vertical but one side slopes at c. 80°. Consequently, the internal depth of the bowl ranges from 54 mm to 76 mm. Internally, the base is flat and very roughly finished.

On two opposing sides a horizontal handle extends from just below the rim. The handles are slightly asymmetrical, the larger being very faintly trapezoidal in shape (L 40.9 mm; W 89.9 mm; Th 30 mm), with rounded edges and a flat end with bevelled corners. Occasional small toolmarks remain on the end. The smaller handle is almost rectangular (L 33 mm; W 81.9 mm; Th 24 mm), with rounded edges. The end is cut to a very blunt, shallow wedge shape on which are occasional small toolmarks. On the sides without handles are two opposing, very shallow vertical grooves (W 46 mm and W 46–56 mm). The vessel rim is thinnest (W 5.6 mm) where it intersects with the grooves.

Preparing to lift the Tullen Bowl (Photo: Lydia Cagney for AMS).

The initial shaping and trimming of the wood into the basic vessel form was completed using axes. Small axes, and probably also chisels and gouges, were then employed to hollow out the centre. There are two distinct types of toolmark visible on its interior: flat facets between which are multiple closely-spaced parallel straight facet junctions (W 23 mm) from a very straight-edged blade, probably a chisel, and slightly convex marks of a wider blade with a very slightly convex edge and rounded corners (min. W 32.5 mm), probably a small axe. (Facets are the individual marks left on a piece of wood each time it is struck with a tool and are often strong indicators of the type of blade used. The junctions between them are also good indicators of the ability of the blade to cut through the wood and can sometimes demonstrate the size and shape of the blade edge.) The base is flat and is also covered with multiple straight facet junctions (L 31–41 mm), similar to those on the walls and spaced 2–5 mm apart. Most of these are orientated lengthwise, parallel to the handles. The exterior of the walls are unevenly covered with flat to slightly concave, subcircular and lozenge-shaped toolmarks (av. L 20–24 mm; W 16–24 mm), between which are very clean junctions. Below both handles are bands of multiple straight facet junctions like those on the interior. Externally, the base is sloped, and several knots are visible in the wood. Toolmarks on the base are unevenly distributed and include some identical to those on the exterior of the walls, but mostly they comprise bands of parallel straight facet junctions (L 36–56 mm; W 1 mm).

Illustrations of the Tullen Bowl (Drawing: John Murphy for AMS).

The exterior of the vessel is covered in subcircular and lozenge-shaped toolmarks which are very typical of prehistoric wooden vessels, on which they are often arranged in parallel bands forming a simple decorative motif. Recent experimental work to create a replica Iron Age vessel from Pallasboy, Co. Westmeath (https://thepallasboyvessel.wordpress.com/phase-1-the-pallasboy-vessel/), led by woodworker Mark Griffiths, demonstrated that these marks are easily created using a gouge, but to arrange them neatly in bands is labour intensive. The marks on the Tullen Bowl are quite irregularly dispersed which, combined with the uneven shape, might suggest that the bowl was the work of an individual with some skill but who was still learning their craft. The two shallow vertical grooves on the exterior appear worn rather than carved, suggesting it was suspended with the grooves created by the pressure and/or friction of a rope. Despite its somewhat uneven shape and finish, the Tullen Bowl was evidently made by a skilled woodworker capable of creating the basic form, hollowing out the centre and shaping and trimming the handles.

Wooden artefact specialist Caroline Earwood has identified a group of carved bowls from Northern Ireland and western Scotland dated to between the first century BC and the fourth century AD. These differ somewhat from the Tullen Bowl in that the handles are mostly triangular and perforated; however, the similarities in form are clear and the date of the Tullen Bowl places it comfortably within Earwood’s group. This suggests the woodworker who made the Tullen Bowl may have been working within a tradition with a distinctly local template but with northern connections and perhaps also cultural affiliations.

Fragments of another bowl (10E328:199:1) were found in remarkably similar circumstances just over 2 km south of Tullen 2 in Lisroyne townland, on the outskirts of Scramoge. Like the Tullen Bowl, it was also found in a large pit interpreted as a well cut into a Bronze Age burnt spread and was made of alder. However, it was of a later date (fifth to sixth century AD) and was turned on a lathe rather than carved.

The Tullen Bowl is a well-preserved everyday object made of alder, a species often chosen for the production of domestic vessels. In early Irish texts, alder is referred to as an Aithig Fedo or ‘commoner of the wood’ and most references to its use relate to making shields, masts, and tent-poles. However, bowls, tubs and troughs found on waterlogged sites are often made from alder. Being a damp species, it holds liquids well and does not impart any flavour to foodstuffs, making it an ideal choice for domestic use.

The Tullen Bowl is an important addition to the corpus of Irish Iron Age wooden vessels and, while it is similar to others within Earwood’s group of carved bowls from Northern Ireland and western Scotland, the shape of its handles and the vertical grooves on its exterior are distinctive. The bowl has been conserved by Susannah Kelly and will be deposited with the National Museum of Ireland along with the other artefacts from the N5 Ballaghaderreen to Scramoge Road Scheme once all post-excavation works are complete. A book detailing all of the finds from the scheme is forthcoming, but readers can learn more from the StoryMap Through Bog & Meadow.

Further reading

Earwood, C 1989 ‘Radiocarbon dating of late prehistoric wooden vessels’, The Journal of Irish Archaeology, Vol. 5, 37–44.

(Posted 29 September 2023)