An Early Medieval Wooden Vessel from Gortcurreen, Listowel, Co. Kerry

By Tony Bartlett and Ross Drummond of Archaeological Management Solutions

Excavations in advance of construction of the N69 Listowel Bypass Scheme in County Kerry led to the discovery of 11 previously unrecorded archaeological sites, revealing evidence of human activity in the Listowel area extending from the Bronze Age to modern times. One of the most significant discoveries was a fragmentary wooden vessel made from yew, found in peat deposits at the site of Gortcurreen 1.

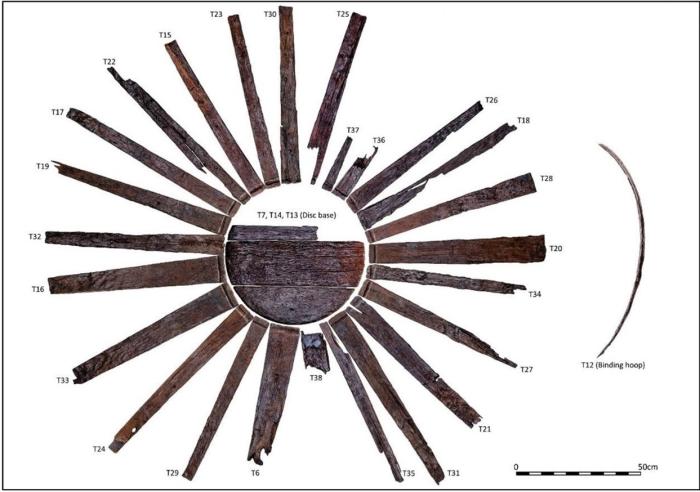

This is a stave-built, conical, open-topped vessel that consists of 25 staves, a portion of a binding hoop, and an incomplete composite base in three parts held together with wooden dowels. The binding hoop, made from a half-split yew, was radiocarbon-dated to the early medieval period (AD 774–950). Also found within the peat deposits were a small number of ex situ oak timbers from an unknown structure. Dendrochronological analysis indicates the trees used for four of these timbers were felled in the ninth century AD.

The remains of the Gortcurreen 1 vessel (Photo: John Channing, AMS).

The Gortcurreen 1 vessel is relatively large, with the longest staves measuring up to 75 cm in length, while the base has a diameter of 53 cm. The presence of a groove (to receive the disc base) on only one end of the staves is indicative of an open-topped vessel. Specialist analysis suggests the vessel was domestic in nature, with its function related to the preparation, storage, and consumption of foodstuffs. It is an example of an object created by the process of coopering—a specialised skill undertaken by a craftsperson. Coopered vessels were made of vertical staves set around a disc, usually held together with external binding hoops of wood or metal, and sometimes also secured with dowels. This process allowed a swifter and more effective method of constructing vessels than in earlier periods.

The vessel pre-conservation, interpreting its construction (Photos: John Channing, AMS).

While no toolmarks could be seen on the vessel timbers, evidence of woodworking was still present. The initial step in the production process was to split the timbers, with the staves being split both radially and tangentially. Following this, axes and adzes, as well as draw knives, were used to shape the staves. The grooves on the staves were probably cut using a gouge. The final trimming of the staves was complicated work carried out with small, sharp knives or hand axes, while the dowel holes in the composite base were likely made using awls.

Interpretive reconstruction of the Gortcurreen 1 vessel (Drawing: John Murphy).

The selection of yew for stave-built vessels may be related to status, as yew is often associated with royalty in the early medieval period and used as a metaphor for wholesomeness. This is a consistent trend noted in the Irish archaeological record, with yew also being favoured for the stave-built vessels found at settlement sites such as Ballinderry Crannógs I and II, Co. Westmeath, Killickaweeny, Co. Kildare, and Deer Park Farms, Co. Antrim.

Differing emphasis and reverence was placed on various types of trees in the pre-Norman Gaelic society of the early medieval period. There are 28 trees and shrubs listed in the eighth-century Brehon law text Bretha Comaithchesa, divided into four hierarchical classes of seven, based on their importance, economic worth, and symbolism. First, there was the ‘lords of the wood’ (airig fedo), followed by the ‘commoners of the wood’ (aithig fhedo), the ‘lower divisions of the wood’ (fodla fedo) and the ‘bushes of the wood’ (losa fedo). Yew (ibar) was considered of particular importance, as it is listed in the ‘lords of the wood’, alongside oak (dair), hazel (coll), holly (cuilenn), ash (uinnius), Scots pine (ochtach) and wild apple tree (aball).

In a ninth-century legal commentary appended to Bretha Comaithchesa, providing a summary of the reasons why the ‘lords of the wood’ were so highly prized, the inclusion of yew is attributed to ‘its noble artefact’, and there is frequent mention of the use of yew wood in the manufacture of domestic vessels. A law text on status includes the ‘expert in yew-work’ (saí ibrórachta) as one of the categories of a craftsman, and in a later legal commentary yew is described as ’the yew-tree of artefacts’ (int éochrann aicdide).

The Lissaniska vessel pre-conservation, following reconstruction (Photo: Ian Russell of ACSU).

A comparative early medieval yew vessel was discovered during recent excavations at Lissaniska ringfort, at Kilcolman, just south of Milltown, Co. Kerry (excavation report available here). The Lissaniska vessel was also identified as a stave-built, conical, open-topped vessel. A sample of wood, taken from the same deposit in the ringfort ditch where the vessel was recovered, was radiocarbon-dated to AD 647–767. The vessel was composed of 12 staves, two binding hoops, and a composite base in three parts. It was also quite large, measuring approximately 60 cm in height, with a basal diameter of 44.5 cm.

The stave-built vessels from Gortcurreen 1 and Lissaniska are very similar, both built through the process of coopering and the composite disc bases of each vessel comprising boards dowelled together. A possible bung or tap hole was noted on one of the Lissaniska staves, just above the base, indicating that the vessel held liquids, potentially relating to either dairying (as a churn) or brewing.

The Gortcurreen 1 vessel is an important addition to the study of early medieval wooden artefacts from rural Ireland. Evidence recovered from the site suggests the occupants were of high social standing within their community and that the container was produced by a skilled craftsperson.

The vessel is currently undergoing conservation, which is being undertaken by specialist conservator Susannah Kelly, and this will be completed later this year prior to its deposition in the National Museum of Ireland.

(Posted 20 March 2023)