Imagining Archaeology Through Art

By TII archaeologists Mary Deevy, Noel Dunne & James Eogan

TII Archaeology & Heritage commissioned a series of reconstruction drawings in late 2013 for inclusion in a number of forthcoming publications. The following images were created by artists J G O’Donoghue and Dave Pollock working closely with archaeologists who have specialist expertise in each of the subjects illustrated. The interpretations presented in these drawings are based on archaeological evidence uncovered on TII-funded road schemes and described in technical excavation reports. An emphasis on being faithful to the excavated evidence was important, however, the archaeological record is often tantalisingly incomplete. It was necessary therefore to be creative and imagine the aspects that were not clear from the evidence discovered at each site. This ‘imagining’ was grounded in current theories and independent research as to what might have been possible in Ireland during the various periods under investigation. National and international parallels were researched and explored in order to fill in these gaps. Nonetheless, in the end the artists and specialists had to combine their skills and knowledge to choose which details to use to tell a story of a point in time in the life of a person, object or place.

Clowanstown, Co. Meath

It is approximately 5000 BC. A man clad in clothing made of fish skin checks the catch in the woven basketry fish-trap that he’s just lifted from the base of the lake. He sits on a simple walkway to which the baskets are tethered. The walkway also acts as a mooring for his dugout canoe, although today his daughter has drifted off in it, distracted while playing with her miniature toy version of the boat. Their settlement is visible in the distance on the opposite side of the lake.

This image was inspired by the discovery of four wooden fish-traps embedded in peat, on the edge of what would have been a small lake in the Mesolithic period (Middle Stone Age). In addition to these highly important artefacts was the discovery of a possible miniature dugout canoe, perhaps a child’s toy. A number of posts pushed deep into the lakebed were found nearby and these have been interpreted as a walkway or mooring. There were few large mammals in Ireland at the time other than wolves, bears and boar. People lived by hunting boar and birds and by gathering wild plants, fruit and nuts; however, fishing would have been a crucial activity. Cultures with a similar reliance on fish, including the Hezhe in China, Ainu in Japan and others in Alaska, have a long tradition of making clothing from fish skins, which make for very soft, comfortable, warm, waterproof and durable garments.

The site was discovered at Clowanstown, Co. Meath, during archaeological investigations in advance of the construction of the M3 Clonee–North of Kells Motorway Scheme. Matt Mossop directed the excavation on behalf of Archaeological Consultancy Services Ltd. Dr Graeme Warren of the UCD School of Archaeology analysed the chipped stone artefacts from the site and kindly provided specialist advice to the artist J G O’Donoghue.

For further information about the Clowanstown fish-traps see Issue 2, Issue 4 and Issue 8 ofSeanda magazine. Read about the Clowanstown fish-traps as featured in Fintan O'Toole's A History of Ireland in 100 Objects.

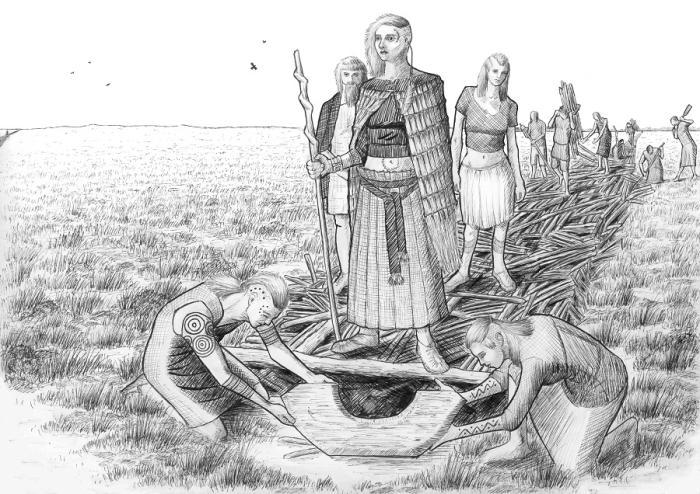

Edercloon, Co. Longford

Three thousand years ago a Late Bronze Age community constructed a wooden trackway in a bog. They laid roundwoods, brushwood and twigs onto the bog surface and secured them in place with long wooden pegs or stakes. Every few metres they deposited wooden objects within the trackway. One of these objects was part of a finely worked, but unfinished, alder block wheel. Another was a twisted and carved hazel rod, like the one at the top of the staff held by the priestess overseeing the deposition in this scene.

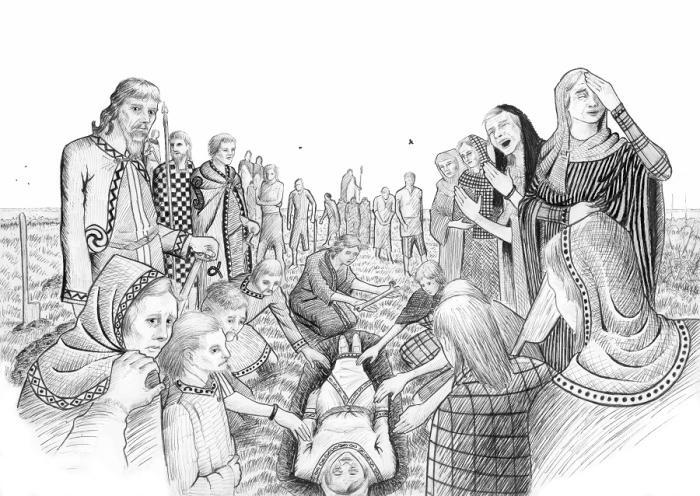

Raystown, Co. Meath

It is the early medieval period, some 1,500 years ago; an elderly woman is being buried in a simple earthen grave within the enclosed cemetery at the centre of her settlement. She is laid close to her ancestors, so close her grave disturbs an earlier burial whose bones are carefully gathered and placed on and beside her body.

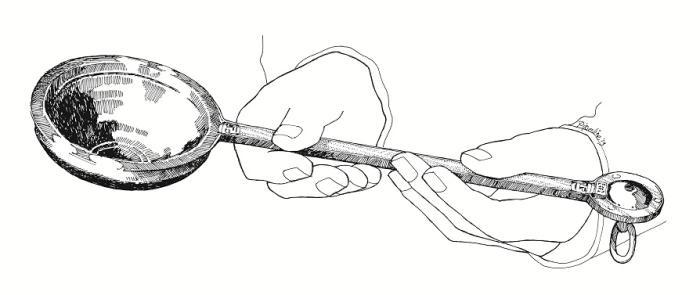

Ballynapark, Co. Wicklow

About 1,200 years ago a beautifully decorated and valuable bronze ladle ended up in a bog. Was it discarded because it was damaged? Was it lost or was it hidden with the intention of subsequent retrieval? Or could it have been a votive offering? The ladle was not whole, but sufficient remains survived to facilitate this reconstruction drawing. Embellishment was provided by the silvery domed terminal, wooden inserts (possibly of yew) along the handle and around the terminal and, strikingly, the opposing human heads at either end of the handle.

Woodstown, Co. Waterford

The first of numerous Viking raids recorded in the Irish annals was in AD 795 on Rathlin Island, but what did these fearsome warriors look like? Using evidence from a grave excavated at the ninth-century Viking settlement site at Woodstown, Co. Waterford, artist J G O’Donoghue has visualised a Viking warrior with advice from Viking expert Dr Stephen Harrison. This is the first time a visualisation has been created of a Viking using evidence from Ireland.