Scholars and Skeletons: A Museum Workshop on Life in Early Medieval Ireland

By TII Archaeologist Martin Jones

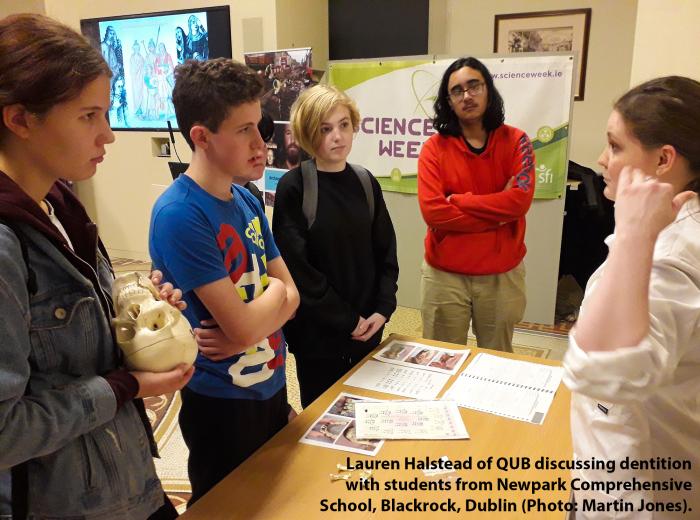

Welcomed at reception and ushered through the crowds, intently examining the wealth of artefacts on display, into a private room at the National Museum of Ireland, Kildare Street, Dublin, one got a sense of the everyday life of the privileged dignitary. These VIPs, however, were not—not yet, at least—political heavyweights, internationally renowned sportspeople, scientific pioneers or famous entertainers. On 15 November 2018, the National Museum of Ireland invited three groups of secondary school students to participate in a Science Week workshop on life in early medieval Ireland. These students, all on the cusp of making choices which will shape their future careers, were from the Convent of Mercy in County Roscommon, and from Newpark Comprehensive School, Blackrock, and Trinity Comprehensive School, Ballymun, both in Dublin.

The From bones to people—life in early medieval Ireland workshop, organised in collaboration with Transport Infrastructure Ireland and Queen’s University, Belfast (QUB), focused on the discoveries at a long forgotten ringfort in the townland of Ranelagh in County Roscommon. Between summer 2015 and autumn 2016, this site was excavated by a team of over 20 archaeologists, revealing evidence of farming, animal butchery and fine metalworking in the early medieval period, as well as more than 1,000 skeletons, thought to belong to the extended family of the ringfort's inhabitants.

Since excavation, these skeletons have been analysed by a team of osteoarchaeologists from QUB using traditional methods, as well as modern scientific techniques, to establish the everyday routines, the many hardships, and the simple pleasures experienced by these people. As part of this special Science Week workshop, students had the opportunity to learn about the site and the early medieval period in Ireland from archaeologists and to take part in hands-on, practical activities—with the assistance of the QUB team—to discover what archaeological and osteological evidence can reveal to us about people in the past. Working with replica human skeletons, and with reference to the remains excavated at the Ranelagh site, students learned how to use skeletal remains to establish important diagnostic information such as stature, age at death, cause of death, and gender.

The students—some, perhaps, the biologists, archaeologists, chemists or osteologists of the future—engaged with the content immediately. The three hour-long sessions seemed barely long enough for them to pose their probing questions and contemplate the responses before returning to the public area of the Museum. This kind of partnership event—combining the practical features of archaeological excavation, the theoretical elements of archaeological inquiry, and the scientific aspects of analysis—seemed, to me at least, to be one of those which was perfectly at home in the National Museum of Ireland.

(Posted 18 December 2018)